Word count: 1621. Estimated reading time: 8 minutes.

- Summary:

- The solar panel mounting kit was purchased from VEVOR for €55 inc VAT delivered each, and it consisted of two aluminium brackets made from 6005-T5 aluminium alloy, with a length of 1.27 metres, depth of 5 cm, and width of 3 cm. These brackets were stronger than expected and could withstand a load of up to 6885 Newtons before buckling.

Tuesday 10 February 2026: 10:37.

- Summary:

- The solar panel mounting kit was purchased from VEVOR for €55 inc VAT delivered each, and it consisted of two aluminium brackets made from 6005-T5 aluminium alloy, with a length of 1.27 metres, depth of 5 cm, and width of 3 cm. These brackets were stronger than expected and could withstand a load of up to 6885 Newtons before buckling.

In the meantime, I’ve been trying to coax my architect into completing the Passive House certification work which had been let languish these past two years as until the builder and engineer had signed off on a completely complete design, there was no point doing the individual thermal bridge calculations as some detail might change. So all that had gone on hiatus until basically just before this Christmas just passed. My architect feels about thermal bridge calculations the same way as I feel about routing wires around my 3D house design i.e. we’d rather do almost anything else, but we all have our crosses to bear and when you’re this close to the finish line, you just need to keep up the endurance and get yourself over that line. It undoubtedly sucks though.

I completed a small but important todo item this week which was to complete the roof tile lifting arm + electric hoist solution shown in the last post by creating a suitable lifting surface. This is simply a mini pallet with the wood from an old garden bench whose metal sides rusted through screwed into it – the wood is a low end hard wood and must be easily a decade old now, but as it had no rot in it when I cut up the garden bench, I kept it and it’s now been recycled into usefulness – though I suspect that this use will be its last hurrah, as all those concrete tiles are going to batter the crap out of it:

As that’s hard wood, it’ll take more abuse than the soft pallet wood, and I even used the rounded edged lengths at the sides to reduce splintering when loading and unloading. I have a lifting hoist I’ll thread around and through it, and it should do very well if we keep the weight under 125 kg which is the limit for the electric hoist in any case.

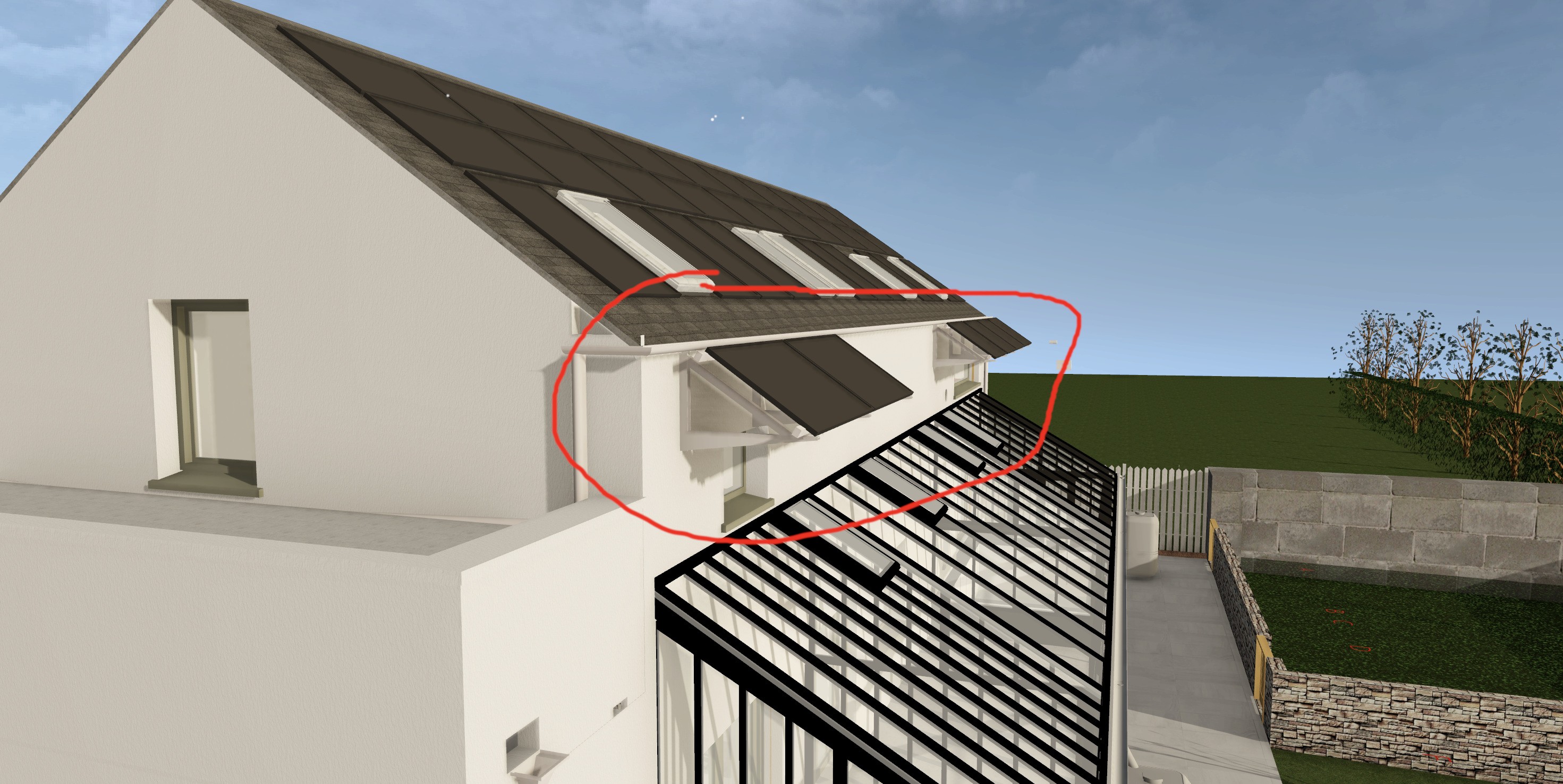

Another a small but important todo item was to solve how to mount solar panels onto the wall. We have six solar panels mounted on the south wall which act as brise soleil for the upstairs southern windows:

In the past three years I had not found an affordable and acceptable solution for how to mount those panels because I specifically did NOT want to use steel brackets, as those would produce rust stains running down the wall after a few years. I had consigned that problem to one that I’d probably have to fabricate my own brackets by hand from something like aluminium tube, so I was delighted to stumble across an aluminium solar panel mounting kit on VEVOR a few weeks ago. For €55 inc VAT delivered each you get two of these:

Actually, the bottom cross bar is an addition manufactured by me from 20x20x1.5 square aluminium tube, but I’ll get onto that in a minute. These VEVOR brackets are made from 6005-T5 aluminium alloy, are 1.27 metres long, 5 cm deep and 3 cm wide. They come with 304 stainless steel M8 bolt fasteners. I very much doubt that I could have made each for less than €28 each, and it would have taken me days to make all of them given I spent six hours making just the bottom cross bars alone. So I have saved both time and money here, which is always delightful.

Which brings me to cross bars. The outer brackets are very strong, and being braced at at least two occasions during their lengths I have zero concerns about them. This raises the cross bar: it is a 2 mm thick 570 mm long profile 30 mm on one side and 20 mm on the other side. Using Euler’s buckling load formula:

… using the appropriate values for 6005-T5 aluminium alloy, and for which I, the minimum second moment of area, is the hardest part to calculate, and for a right angle length I reckon that is:

… you’d expect a maximum load before buckling of: 6885 Newtons.

(I checked my minimum second moment of area calculation using the much less simplified https://calcs.com/freetools/free-moment-of-inertia-calculator, and it is about right)

6885 Newtons looks plenty strong enough. Let’s check it: the solar panels have an area of about 1.8 m2 and can take a wind load of up to 4000 Pa before disintegrating. We would have five brackets for four panels so our design load needs to be 4000 Pa x 1.8 * 4 / 5 = 5760 Newtons. If the crossbar were at the far end, you would halve that load between the top M8 bolt and the bottom crossbar, but because we’re mounting these on a wall and not on the ground, and because we need the panels to be at a 35 degree angle, the crossbar HAS to be most of the way up the two side arms. Indeed, if you look again at the photo above where the angle is correctly set to 55 degrees so the panels are at 35 degrees, the crossbar is about one third from the top. This is effectively a lever, and I reckon that it would amplify the force on the crossbar by about double, which would buckle it if the panel ever experienced a 1673 Pa wind gust.

Here are the worst recorded wind gusts ever (with pressure calculated by (P = 0.613 × V2):

- Worst in Ireland: 184 km/hr, 51 m/s = 1594 Pa

- Worst on land: 408 km/hr, 113 m/s = 7827 Pa

- Worst hurricane at sea: 406 km/hr, 113 m/s = 7827 Pa

- Worst tornado: 516 km/hr, 143 m/s = 12535 Pa

However, at an angle of 35 degrees, 0.57 of a horizontal wind pressure would apply to a panel, so not even 1000 Pa would ever land on a panel in the worst wind gust ever recorded in Ireland. So on that basis, that little cross bar should be more than plenty in real world conditions.

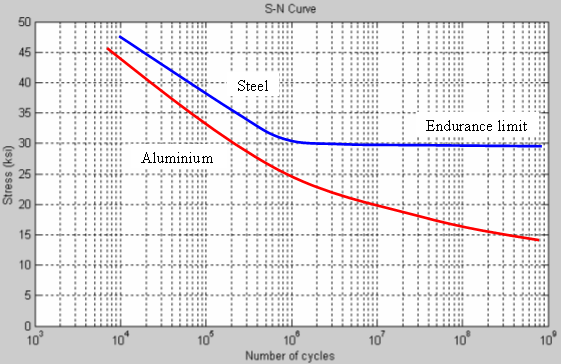

If these were steel brackets, we’d be done, but steel is unusual in the world of materials: it has a weird fatigue endurance curve. I’m going to borrow this graph from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fatigue_limit as it’s hard to explain in words:

Fatigue endurance of steel compared to aluminium over stress cycles

Most materials are like aluminium in that as you repeatedly flex them, their strength decreases as the number of flex cycles increases. This makes sense intuitively: imagine little tiny fibres in a rope breaking with each flex, and over time the rope loses strength. Steel however greatly slows down its strength loss after a million flexes, which is one of the big reasons so much structural stuff in modern society is made from steel: almost nothing as cheap and easy to mass produce as steel has this property. Hence your cars, houses, bridges, screws, bolts, nails etc anything which sees lots of repeated flex tends to be made from steel. Why is steel like this? It comes down to orientation of crystalline structure, but I’m getting well off the reservation at this point, so go look it up if you’re interested.

In any case, my brackets will be up in the wind getting repeatedly flexed, and that little cross bar would be getting flexed a lot. So while it might last five or even ten years, I had my doubts it would last until my death and those brackets will be an absolute pain to get to once the greenhouse is up. So I decided to add a second, longer, crossbar which you saw in the photo above.

For that I purchased eight one metre lengths of raw 20x20x1.5 square tube made out of 6060-T6 aluminium alloy. 6060-T6 is about half as strong as 6005-T5, but it didn’t matter for this use case and it was cheap at €4 inc VAT per metre. I drilled out holes for M8 stainless steel bolts, and voilà, there is the bracket above which is so strong that me throwing all my body weight onto it doesn’t make it flex even in the slightest. No flexing at all in any way is the ideal here as it maximises lifespan, so only the very slow corrosion of the aluminium will eventually cause failure.

Out of curiosity I calculated this second crossbar’s buckling load:

A 304 stainless M8 bolt will shear at 15,079 Newtons, so the top bolt of the bracket is fine. Assuming an even distribution of 5760 Newtons, that is 2880 Newtons on each end, a safety factor of 50% if the middle crossbar were not fitted. If I were not fitting the middle crossbar, I probably would have used 25 mm sized tube, because buckling strength is related to dimension cubed, it would be a very great deal stronger.

I will be fitting the middle cross bar however, but more to prevent any side flex of the side brackets than anything else. The far bigger long term risk here is loss of strength over time due to flex, and that middle cross bar does a fabulous job of preventing any flex anywhere at all. In any case, this bracket is now far stronger than necessary, it would take a 12 kN load which is far above when the panels would fall apart. I think they’ll do just fine.

| Go to previous entry | Go to next entry | Go back to the archive index | Go back to the latest entries |