Word count: 25032. Estimated reading time: 118 minutes.

- Summary:

- A detailed historical narrative spanning 1815-1915 is presented, tracing how one branch of the author’s family lost their fortune derived from Caribbean sugar plantations. The decline of landed aristocracy through economic shifts, policy changes, and poor investment decisions is examined. Parallels are drawn between that era and current times, with speculation offered about AI’s role in creating a new technological aristocracy and its societal implications.

Friday 9 January 2026: 00:26.

- Summary:

- A detailed historical narrative spanning 1815-1915 is presented, tracing how one branch of the author’s family lost their fortune derived from Caribbean sugar plantations. The decline of landed aristocracy through economic shifts, policy changes, and poor investment decisions is examined. Parallels are drawn between that era and current times, with speculation offered about AI’s role in creating a new technological aristocracy and its societal implications.

This essay is about how my personal family, especially one branch of it, got from where they were at the beginning of the Second British empire, which began after the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, until now. The period 1815-1915 is peculiarly similar to the period 1945-2045 (so far) with a remarkable repetition of resonances, so what keeps drawing me back to thinking about that earlier period is due to me thinking hard about what is to come next for us right now. Yes, we know the broad sweep of history from the history books. But in terms of knowing what to do for my family now and next, personalising history into the context of my historical family from the 1815-1915 period seems worth doing.

Also, to be honest, AI has just very recently revolutionised parsing

historical records. I had always assumed that record keeping before the 20th

century just wasn’t very good. In fact, record keeping since 1750-1800

onwards has been surprisingly complete in most of the western world, it’s

just that the data was locked in hard to parse records distributed across

many small places. AI in the last few years has become better than certainly

this human’s ability to decipher ancient hand writing, which has turned all

the digitised old records into far more useful resources because now the

text extracted from them is accurate, but also because AI can then summarise

that extracted text into comparable text corpora. Also, there has been a

concerted effort to digitise things like headstones in cemeteries, and with

all that information sites like ancestry.com

have made it surprisingly

straightforward to assemble your entire complete family tree going back to

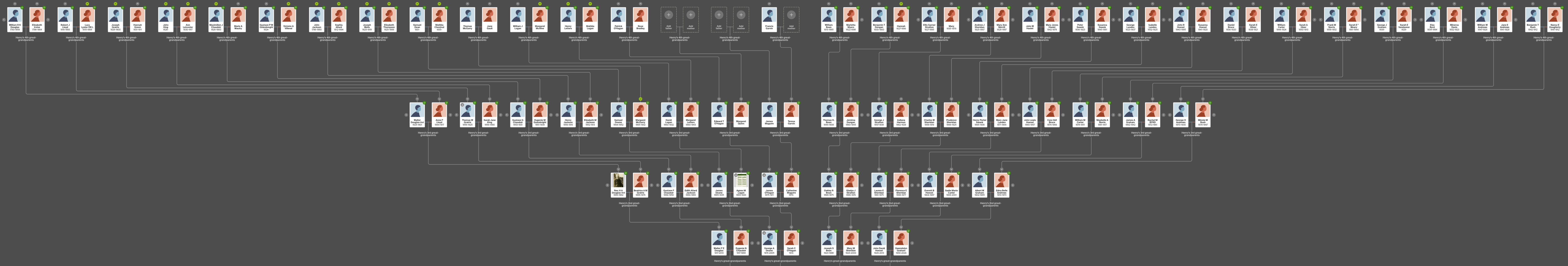

1750 or so. To that end, here are the sixty-four sixth generation away

people who contributed genes to my children (and my thanks to my Aunt Ruth

and Megan’s mother Sara for getting me started with creating this tree),

and my apologies in advance if your web browser doesn’t yet support the

experimental scroll-initial-target:nearest CSS feature to initially

scroll this very wide PNG to centre on page load (if it doesn’t, you’ll

need to scroll this image right to reach the centre):

There are five people missing – this is because ancestry.com wants me to pay them money to establish those, and because I don’t want to pay them money, I’ll be leaving those empty until the ‘free ancestry.com lottery’ gives me them for free (to drive engagement, they drip feed you free data each day to make you log in frequently). But I can tell from their advertising being pushed at me that they have the data not just for those missing five people, but also certainly their parents and possibly their grandparents. So, given enough time or paying ancestry.com money, I think I could create a reasonably probably complete list of the 256 people which make up the eighth generation away ancestors. That’s pretty good – that’s everybody from about 1750 until now, so 275 to 300 years, barring a few likely mistakes where I’ve misconnected children to parents. Within that list, I know birth, death and marriage dates, the number of children and number of spouses, but I often also know occupations, and a surprising amount about internal and international travel (before the 20th century, immigration logs were public, but also children’s birth certificates state location).

The picture which emerges from our complete set of ancestors is very much representative of European colonial imperialist expansion during that period. As that will also set the stage prior to when this essay will begin in earnest from 1815 onwards, it is worse briefly recounting.

What our ancestors were doing towards the end of the First French Empire (before 1815)

What AI thinks British Colonial America looked like before independence

Megan’s side of the family before 1815

In terms of percentage of new arrivals relative to the existing population, the United States has had three historical bursts of immigration:

- 1600-1770 (pre-independence), after which immigration was near zero until …

- 1830-1900 much of which was driven by famine in Europe followed by the Long Depression, after which …

- 1950-2010 was driven by the United States replacing Britain as the dominant world economic hegemon, and therefore attractive to global economic migrants.

You can read lots more detail at the Wikipedia page on the history of immigration into the United States, and no I didn’t mistype the third burst ending in 2010 – most US citizens currently think floods of immigrants are entering right now, but the statistics show that the third burst did indeed peak in 2010 and since then ever fewer people relative to the current population have relocated to the United States. If history repeats, it’ll be another fifty years before the next burst begins.

Interestingly, most of my wife’s ancestors were already in the US when it was still a British colony, so they arrived during the pre-1770 immigration period from what appears to be mostly British Presbyterian stock (who at the time were being persecuted for their religious beliefs). That was surprising to me and to her – she had thought herself comprised more of post-1830 immigrants. Yes there are a few of those in her bloodlines, but the bulk is undoubtedly the many young British people who sold themselves into indentured labour to pay for transport to the colonies with the hope of better economic opportunities. After their indentured contract was served, they generally purchased farmland typically around Maryland, Carolina and Virginia where cash crops for export were grown. One thing very noticeable on Megan’s side of the tree is the number of children her ancestors had who survived into adulthood compared to my side of the tree – also, whereas a majority of the women my side of the tree died in childbirth, on her side I’d estimate two thirds or more made it into relatively old age. This suggests that while life was hard in the United States, it was worse in Europe, at least for our ancestors. Another thing which stands out is that in my side of the family, there was always the ‘youngest son’ or ‘junior branch’ problem because the eldest sons would get all the inheritance, so special effort and arrangements had to be made to find livelihoods and wives for the youngest sons. In contrast, in Megan’s side of the family all the children bought farmland no matter how senior or junior apparently with relative ease – I would assume that unlike in Europe where all the land was taken and very little was available for purchase, in the US at that time you simply took new land from the native inhabitants which made it affordable to all children.

Indeed, the state of Indiana is so named because it was originally part of the Indian Reserve of 1763 (about which you can read lots more here). That area underwent a period of violent instability caused by British and American armies fighting each other and the native tribes up until 1812 when the British yielded, and the US Congress sought to ensure a bulwark against any further instability going forwards. They made available lots of farmland on the now disentailed Indian Reserve at low prices, and a majority of Megan’s ancestors appear to have taken up the offer – there is a noticeable movement all at once from all over then British Colonial America of all the generations whose children and grandchildren were yet to marry each other to lands within or nearby the state of Indiana. And there they have remained ever since, with surprisingly limited relocation until very recently, mainly growing food or providing services to farmers such as religious guidance (mainly Lutheran), blacksmithing or dentistry for about two hundred years. As far as I can tell from this vantage point, there wasn’t a huge disparity in economic outcomes across all Megan’s ancestors – they all appear to have started from roughly similar circumstances, some were a generation or two earlier to wealth and education and moving up the value chain than others, but they all moved with remarkable uniformity relative to my ancestors who are far more a hotchpotch. I guess that’s what the American Dream once was: most bar the dispossessed native inhabitants had things, on average, better than their ancestors for enough generations it became an expected truism.

My side of the family before 1815

Megan’s ancestors were remarkably uniform, whereas mine are quite the smorgasbord. Like Megan’s ancestors, one quarter of mine on my Presbyterian mother’s father’s side at that time were also low church Protestants of varying kinds. I can see brothers and sisters of those ancestors emigrating to America and the other British colonies, however obviously my specific ancestors did not. As far as I can tell, the reasons mine stayed were because they were the eldest or second eldest son and thus had an inherited livelihood, or else they married an eldest or second eldest son. As with Megan’s ancestors, men tended to reach their seventies and the women who didn’t die in childbirth usually made their sixties. Subjectively speaking, it looks like life around 1800 was a bit better for the Americans than for this quarter of my ancestors, but only by a bit.

A second quarter on my Catholic mother’s mother’s side did not do well, at least as far back as I can currently see. My grandmother’s father, a gardener for a priest, died in his forties. Even before that during the 19th century, they were lucky to make it into their fifties before death, and life was hard – I can see they had to share a small house with another poor family in the 19th century. They still had it better than many on the island of Ireland at the time – you didn’t want to be a sub-sub-tenant farmer as an example, they were mainly the ones who died from starvation in the potato famine. They were so poor that there were no choices other than to starve to death – emigration was an option only for the slightly wealthy upwards. This branch of my ancestors weren’t that poor, they were maybe one or two rungs above, they definitely could afford an occasional steamer to America – as evidenced by the location of my great grandfather’s demise (San Francisco).

The next quarter were mostly Catholic on my father’s mother’s side. They were a mix of middle class Catholic French Belgians and middle class Protestant probably Methodist English from Suffolk, with jobs such as tailor, composer or teacher. They generally had long healthy lives and had sufficient wealth that all of their relatively few children (by the standards of that time) who reached adulthood could be well educated and given a good start in life. Indeed if you squint a little (childhood mortality was high back then), the children born around 1800 to that quarter of my ancestors had a similar lifestyle to middle class people today – they travelled quite a bit for pleasure, attended leisure activities such as orchestral recitals, and clearly felt a security about life and living which the previous two quarters of my ancestors never knew. The only major obvious difference is rates of childhood mortality, otherwise they look surprisingly contemporary in terms of behaviour, pastimes and inclinations, at least from this distant perspective.

What AI thinks is 'aristocracy'

The final quarter is by far the best documented – mostly due to the work of my Aunt Ruth thank you! – but also because they were famous at the time due to being either aristocracy or wealthy, and hence lots of ink got spilled about them in lots of places over the centuries in everything from wood carved caricatures to tax receipts. Back in 1800, two of my ancestral lines combined, one was aristocratic, well regarded, and sometimes wealthy but generally plagued with money troubles; the other until now we had thought were wealthy industrialists my ancestors had married into, but I now think were actually also ruling elite but recently dispossessed of their power which caused them to take a big gamble which paid off, but at the expense of thousands of lives – all the other bloodlines they married into were usually middle class with good jobs like the previously described Catholic quarter – though generally Anglican/Methodist/Lutheran Protestant rather than Catholic. Of the aristocratic bloodline, let us begin with my specific ancestor Sir William Douglas (1730-1783) who was a Member of Parliament for Dumfries between 1768 and 1780, and you can read his Hansard history here. Before 1833, most members of Parliament for a given constituency were chosen by the big landowners of that constituency, which in this case was primarily Charles Douglas, Duke of Queensbury. To be clear, a Member of Parliament back then did NOT work for the people, they worked for and had their salary paid by the big landowner, and they had to do what they were told or they were replaced. The Duke was very keen on my ancestor William who also ran his estate for him as a manager, and left £16,000 to him on his death in 1778, an enormous sum (about £39 million in 2024 sterling by the wages deflator).

Sir William Douglas (1730-1783)

William until that point had never been wealthy. His father, Sir John Douglas, also Member of Parliament 1741-1747 but for Dumfriesshire which neighbours the Dumfries constituency, had died in disgrace in debtor’s prison, which was almost never used on members of the aristocracy except in the very most severest and recalcitrant cases (he also got himself locked in the Tower of London pending execution for High Treason against the Crown in 1746, but I digress). William and his siblings, having had no other members of family willing to take them in, ended up being raised with his tutor’s family which was not a wealthy upbringing, and William had to take a job which was as manager of the Duke’s estate and succeeding his father’s role Member of Parliament for that constituency – so he worked for a living and had done so all his adult life. Unfortunately, so overjoyed was he on receiving such a life changing sum of money after a lifetime of severe money issues, he had a fit of apoplexy and died upon receiving the good news. That inherited fortune then formed the basis for his eldest sons’ livelihoods, which meant that my specific ancestor Lord William Robert Keith Douglas (1783-1859) who was the youngest son (and therefore without a livelihood) therefore also needed to take a job like his father. By the time he was an adult, his patron who had inherited the previous Duke’s lands and titles was Walter Francis Montagu Douglas Scott, Duke of Buccleuch and Queensbury, the richest man in Scotland (an actual millionaire in the money of the time, the current Duke who is that Duke’s lineal descendent remains today the richest man in Scotland owning about half the total land area). This Duke did not like my ancestor as much as the previous Duke and often grumbled publicly about him, however he still sent him to Parliament for Dumfries between 1812 and 1832 after which the rotten borough system was abolished, and Hansard has written up an excellent summary of his political life here.

The younger Douglas was considerably more active in Parliament than his father, of which there is no record of him ever speaking in any debate ever. He was initially a pro-Catholic, pro-reform, pro-free trade member of the Tory party, and seems to have had enough talent at it that he became noticed by Walter Irvine (1747-1824) as a potentially suitable husband for his eldest daughter, Elizabeth Irvine (1798-1864), which brings me onto the most sordid and sad part of my ancestry.

John Irvine (1720?-1786), the father of Walter, was a Chancery Clerk in Edinburgh, which then was a civil servant who manages the local legal affairs of the monarch, and is custodian of the seal of the monarch for that locality. Such an establishment role is surprising to me for somebody with the surname of Irvine, as that clan’s leading people were strongly associated with Jacobitism. We know John’s family came from around Kingscairn Mill near Crail just north of Dunino in Fife – this is why later they would buy all the lands surrounding there in the form of the Grangemuir estate. We know several other Irvine families lived in a cluster in lands immediately adjacent, and those definitely were involved in the 1745 Jacobite rising because we have records of it. John’s father (probably also called John) had enough money to afford to educate and send his son to Chancery Court, which suggests something better than a tenant farmer. But I’ll speculate on that later.

John Irvine (1720?-1786), or more likely Sir John Douglas (1708-1778), taken by me during Christmas from the painting hanging in my father's house

(The person in this mid 18th century painting is wearing a type of wig called a ‘peruke’, which suggests an occupation in law. It was therefore assumed that this is a painting of John Irvine as he would have worn such a wig at the Court of Chancery. However my grandfather disagrees, and thinks this painting is actually of Sir John Douglas, the same one incarcerated for High Treason in 1746. I have compared this painting to other paintings of Sir John, and I agree that there is a resemblance. Why Sir John was wearing this particular wig at such a young age I cannot say)

A Clerk of the Chancery would have been a very solid upper middle class role with access to and visibility into ruling elites and their information, and with enough income that investing it would be both a concern and a possibility. The Treaty of Paris 1763 brought several Caribbean islands under the control of the British after a century of them being repeatedly re-conquered by Dutch, French and British navies, and to establish a bulwark against another invasion the British government divided the island into plots and sold them to retail investors (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Tobago for detail). John Irvine along with his sons John, Charles and Walter took out a mortgage from a London financier named Mr Rustin and entered a partnership with a Mr Leith to purchase and for the sons to personally occupy a few of these plots in 1768. They then purchased and proceeded to expire thousands of African slaves to work the land to grow cotton, without much profit. A banking crisis in London in 1772 put many of the planters into financial hardship; in 1778 the partnership with Mr Leith was broken up as the economic situation worsened due to war in the American colonies; in 1781 the French recaptured Tobago, and at this point a majority of the original planters gave up and sold what little value remained. My ancestors Walter and Charles (by then their brother John had died from suspected malaria) proceeded to buy up all this land at firesale cheap prices to create very large plantations which would shortly greatly benefit from economies of scale.

It would appear the bad times continued for them until the 1789 French Revolution which spread disarray throughout the French colonial empire, and specifically the most profitable possession in the French empire Saint-Domingue, today known as Haiti. Production across the French Caribbean collapsed over the next few years, and my ancestor in possession of large, very efficient, estates in Tobago was unusually well placed to benefit from it. In the next ten years their plantations switched over to sugar and rum production, and over a quarter billion pounds in today’s money was pocketed as profits by the two brothers in a few short years. If this seems fantastical, consider crypto billionaires today: the vast majority of people who were involved in crypto before it ballooned never made anything from it. A few very lucky – and I want to emphasise it was luck not skill nor hard work – people just happened to be in the right place and right time to receive an enormous windfall, and had any one thing been different they would have gotten absolutely nothing. Like crypto billionaires today, my ancestor was astonishingly lucky (in financial terms). Using his new found vast wealth, in 1796 he purchased Luddington House from a Richard Wyatt of Egham as his British residence, a very fancy property, in Surrey south west of Heathrow Airport. This is it today (it is now an apartment complex) and it retains all the original 17th century buildings and layout, as it is a protected building:

Luddington House today which is home for lots of families; in 1800 just one family (and their servants) lived in all those large buildings

Indeed, such were the profits from the sugar plantations that the British government swiftly imposed steep import tariffs to capture much of those profits and thus removing that windfall from the sugar plantation owners (in those days, most government income came from tariffs and duties, income taxes were only levied during times of war). My ancestor Walter Irvine realised he now needed to be near London to protect his interests against further government intervention, so in 1796 he moves permanently to Britain into his new house, and the following year marries Catherine Gordon, the second eldest daughter of a neighbouring Tobago plantation owner Alexander Gordon, with him aged fifty and her aged thirty-two. I’ll do some speculating on her later, but almost certainly Walter would have known Catherine for some years before marriage as the Tobago ‘dinner party scene’ involved the wealthy having parties in each other’s houses throughout each year, and I can find no reason why as neighbours the Irvine and Gordon estates would not have socialised with one another. In 1798 his brother Charles dies intestate, so Walter ‘ends up with’ all the plantation wealth (I put that in quotes, because a later legal case alleged he purloined his brother’s estate for token payments to his brother’s family). He then proceeds to use that vast wealth to influence government direction, successfully stalling for fifteen years what would become the Slave Trade Act of 1807 in the House of Lords after it was originally passed by the House of Commons in 1792. It was probably only eventually released out of the Lords because of events on the Continent, where Britain sought a moral win over the rising Napoleonic empire, and that gave the abolitionists enough momentum to get it out of the Lords and into law. Now that the trading of slaves was illegal from 1807 onwards, that began the end of the slave plantation era which would take another century to be fully enacted.

According to the West-India Commonplace book report published in 1812, up to 1807 the two least worst for the slaves plantation islands in the British Caribbean were St. Vincent and Tobago in that order. In both, due to how they were set up and planted by mostly Scots mostly junior branches of aristocratic or merchant families, a culture of investment in machinery, automation and the education and training of the slaves to maximise profits had taken hold, rather than maximising profits by working them to death which was common elsewhere. As that report describes, unlike in the other islands, in both islands the population were usually well treated enough to grow naturally and therefore exported surplus slaves to the other islands, the worst of which would annually kill 2-4% of their slave populations from overwork and therefore needed to constantly buy more to remain viable. Unlike elsewhere, in St. Vincent and Tobago the managerial class of slaves were routinely taught to read and write and could accumulate assets which could then be used to buy their own or another’s freedom, or willed to others on death. That report reckoned from a purely economic perspective that St. Vincent and Tobago’s practices as best in class due to being the most productive once all costs were considered, and that their practices should be replicated elsewhere. Thanks to an enthusiastic society of local historians, Tobago has since built up an extensive and detailed academically researched history of the plantations on their island, and a good summarising book on that research can be found in 2008’s The Changing Society of Tobago, 1838-1938: A Fractured Whole, which can be downloaded and read in full from here. Where later I make statements about life in Tobago, it will either come from that book or from the Tobago historical society’s Facebook group.

I don’t want to make the relatively better conditions on Tobago sound like any form of excuse making for this branch of my ancestors. Walter Irvine had at least one child named Betsy from his slaves before he married Catherine Gordon, and could have been the father of a second named Mary. Catherine, his future wife, would almost certainly have known both daughters personally for some years before marrying Walter, and it appears to have not been a showstopper for her – slave master men having children with their female slaves was quite common in Tobago and indeed in most of the colonial plantations. Both girls, especially Betsy, received life changing fortunes from his will on death, and Betsy who comes across as a favourite relocated permanently to Britain with him in 1796 aged eight and stayed there until at least his death in 1824. Possibly, Betsy’s mother had died during childbirth, as Walter’s will awards a fine cash sum to Mary’s ‘negro mother’ (I quote here from the will), but no mention of Betsy’s mother was made. We haven’t found evidence that Betsy ever married, but Mary did marry and she is the ancestor of a good number of people living throughout the Caribbean today.

Walter’s main plantation is today a luxury resort hotel owned by a descendent of slaves who worked there with all the sugar plantation buildings and machinery preserved as features – the sugar mill, once the largest on the island, now houses the hotel restaurant, and the loading docks on the beach for the transport ships have been converted into a promenade for sun loungers. Here it is today:

Mount Irvine, Tobago

Obviously it was rather more grim in 1790, but I have been unable to find a realistic drawing or painting from that early – drawings and paintings from then were heavily sanitised and not at all representative. The most realistic I can find is from around 1900, long after slavery was abolished and by which time almost all the plantations were owned and operated by former slaves and much labour saving automation had been introduced. Still, it’s better than nothing, and all these are of Tobago and thanks to the Tobago Historical Society:

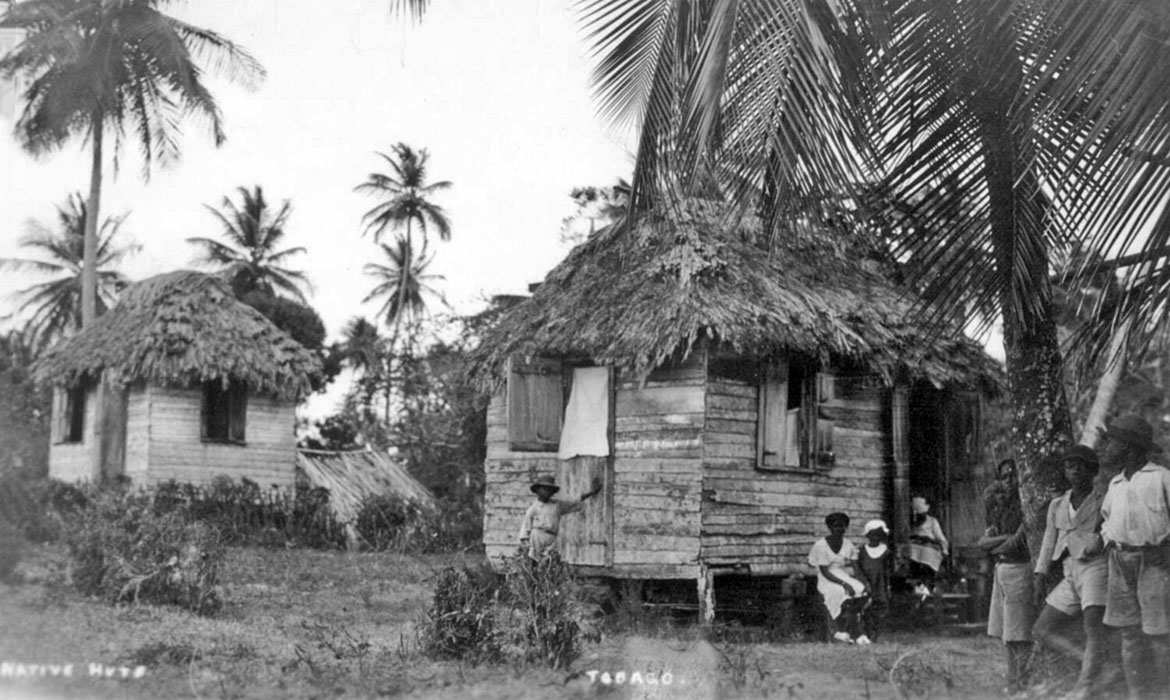

Where the sharecroppers slept around 1900 in Tobago |

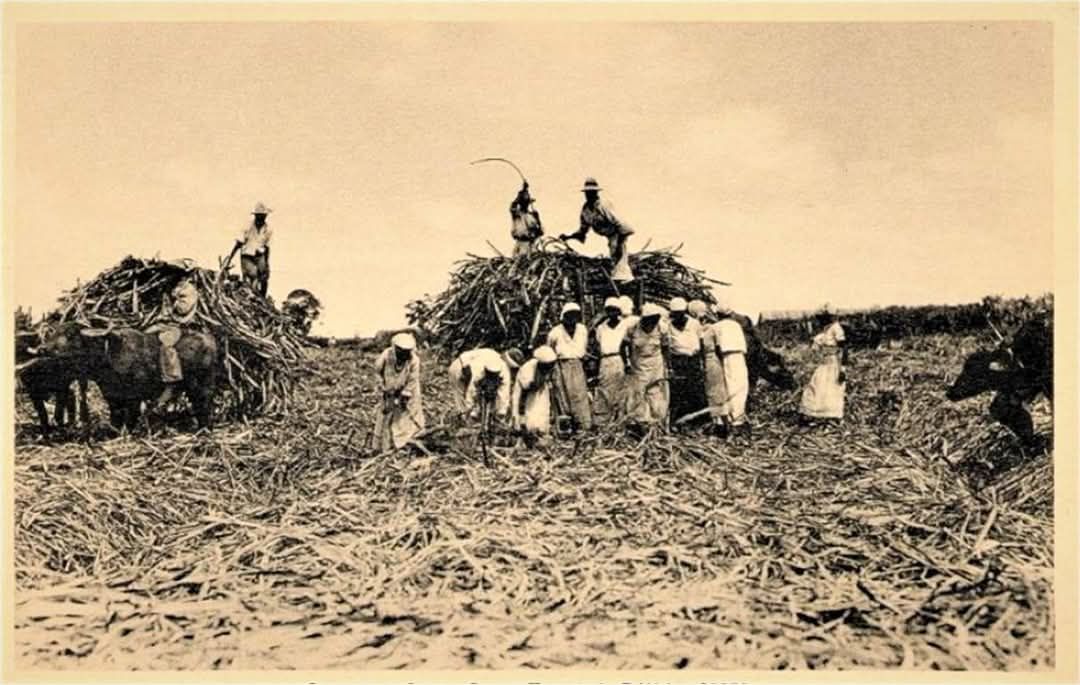

Loading the cut down sugar cane, also around 1900 |

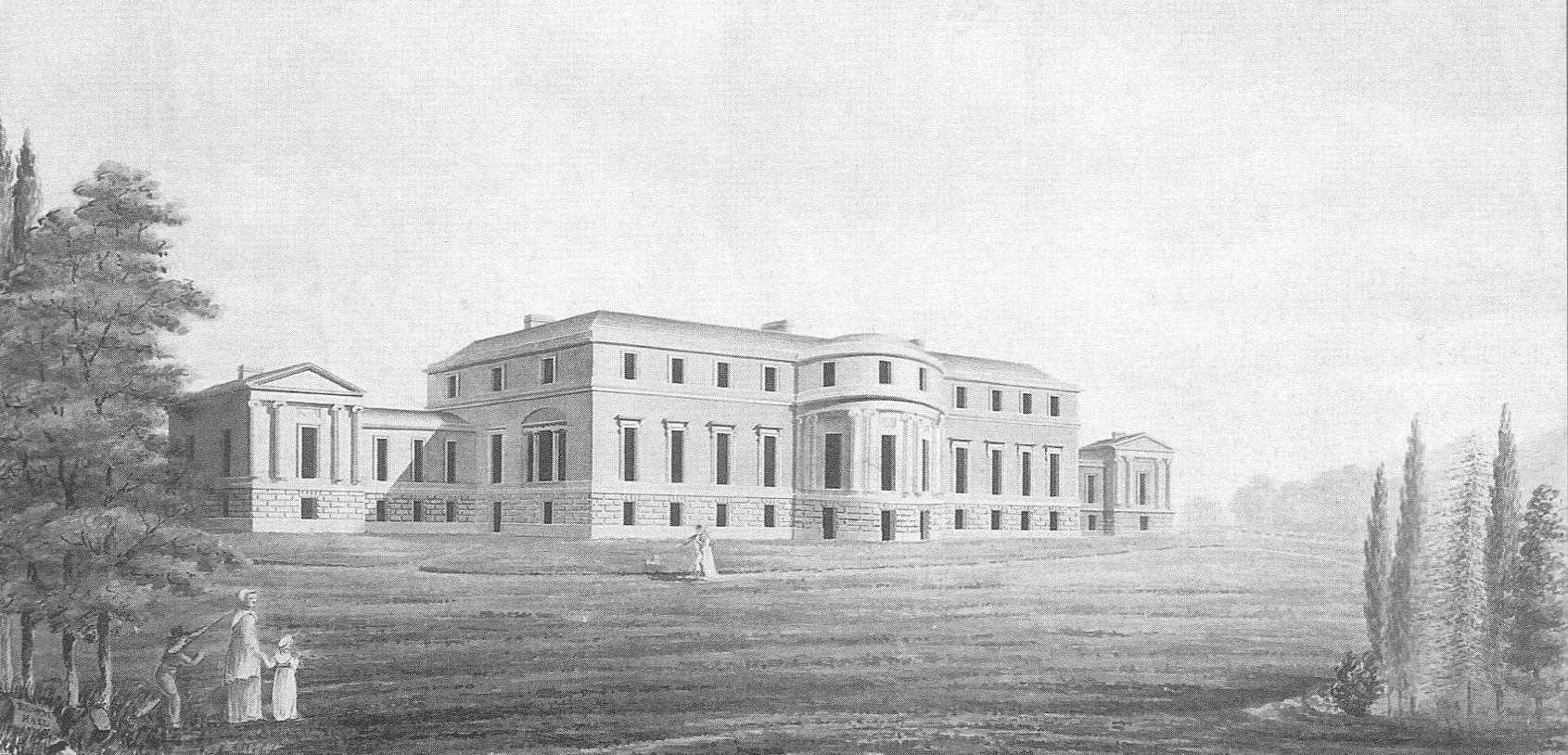

An example of where the plantation owners lived in comparison to the sharecroppers |

To wrap up this section, I’d like to engage in some pure speculation. I find it worth remarking upon that an Irvine marries a Gordon, and their child marries a Douglas. The reason for this is history: my junior branch Douglas ancestors without doubt were managing the same estate of the Duke of Queensbury as similarly junior branch Irvines in the mid 18th century. They were both employed by the Duke at the same time in the same place in the 1760s – this is documented fact. I also found some evidence that junior branch Gordons were also present in the 1760s on that estate at least some of the time, also in a working capacity. Where I would speculate is about the milieu of interaction between all these junior branches – the leaderships of Irvine/Irving, Douglas and Gordon clans had all been by each other sides for centuries beforehand, with very extensive intermarriage and interrelationships both business and personal. That would have spilled into the tenant farmers, or at least their ‘tacksmen’ (the managerial class). There was without doubt a wide network of second and third cousins at least some of whom regularly interacted. Where I speculate is to what extent, and how much it meant to them to ‘marry within’ versus ‘marry out’? To what extent did the ambitious of these junior branches set out to advance the British Empire and their own wealth? How much did they collaborate as a network of Scotsmen and Scotswomen in doing so?

I have absolutely no idea if John Irvine Sr was a tenant farmer under an Irvine chief with no blood ties to that chief and had simply taken the surname, or if a junior branch of the Irvine clan leadership thought it best to vacate their ancestral lands in Drum or Dumfries and ‘disappear’ into Fife (where historically there are zero Irvines) after the 1715 Jacobite rising went against them. We do know a wealthy John Irvine was married to a Helen Ross in Dunino in 1726, and there is no mention of any Irvines in that locality before that date. It would of course, at the time, been wise to not mention loudly their origins, and my John Irvine working at Chancery Court would definitely not want to ever mention at work the word ‘Jacobite’. I suppose we will never know for sure what type of Irvines they were, still:

- The Jacobite rising of 1745 had ended the old Clan system which had rendered impotent all the Clan Chiefs thereafter – also, the Scottish independence movement was now clearly spent. The dispossessed children of clan ruling elites of Scotland began to look outwards to secure their futures.

- There were Douglases, Irvines and Gordons all in the same place in the 1760s,

barely two decades later.

- The Tobago plantation opportunities appeared towards the end of the 1760s and

various Douglases, Irvines and Gordons all took up the offer.

- The Tobago dinner party scene had all these junior branch members regularly

getting drunk together, where almost certainly shared clan history and Scotland

would have been a frequent topic of discussion.

- After fortunes were made, at the end of the 1790s an Irvine marries a Gordon (who herself was the junior branch aristocratic product of a Gordon and McCulloch), and twenty years after that their child marries an aristocratic Douglas. That does strongly hint that these Irvines were former clan leadership who were disillusioned or dispossessed by the 1715 rising, and now were marrying into the Scots side of the British aristocracy.

To be clear, I am 100% speculating here, there is no proof I can find. It just seems remarkably coincidental that some Douglases, Irvines and Gordons definitely were all in the same place in the 1760s just before they bought plantations in the colonies – though, again, there is no proof that it was our specific people bar Sir William Douglas and his children at the Duke’s estate at the time. And those Scots aristocratic junior branches would go on to marry off each other’s children during the next sixty years, which feels like there was at least some ad hoc plan or at least mutually shared direction to all embark upon.

To end on even more specious speculation, I wonder what the psychological effect of repeated defeats of Scots independence across a century were on the strongest believers? Did they take their frustrations and bitterness and become a tip of the British Imperial spear, doing to colonised peoples what the English had done to the Scots for so many centuries? I wonder if all those junior branches of all those leading Scots clans ended up doing what they did to slaves repeating exactly what had been done to their ancestors as some sort of trauma induced repeating loop? It’s all very, very sad.

1815-1915: Pax Britannica

What AI thinks 'Pax Britannica' looks like

So now we’re getting into the meat and bulk of this essay: the century of Pax Britannica, a period of sustained lack of major war caused by a single hegemonic power dominating everything around it. To remind readers of why I find resonances between that period and our own Pax Americana 1945-2045 beyond the sustained lack of war:

| Pax Britannica | Pax Americana | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1815 | Pan-European (Napoleonic) War ends | 1945 | Pan-European (Second World) War ends | |

| 1874 (+59 years) | Long economic depression begins as post-war economic expansion falters | 2008 (+63 years) | Long economic depression begins as post-war economic expansion falters | |

| 1890 (+75 years) | Germany begins to remilitarise in earnest | 2025 (+80 years) | Germany begins to remilitarise in earnest | |

| 1899 (+84 years) | Other European powers begin to remilitarise in earnest in response | Est. 2030-2035 | Other European powers begin to remilitarise in earnest in response | |

| 1914 (+99 years) | Pan-European war begins | Est. 2045-2050 | Pan-European war begins | |

So we have twenty to thirty years remaining before the third World War begins, if the pattern holds. And in case it isn’t obvious why other European powers would begin to remilitarise in earnest in response to German remilitarisation, it’s because due to European history all the other European powers get nervous when Germany has a bigger military than they do. Right now in 2025 Germany has a much less powerful military than any of France, Germany or Spain. But as they keep pouring 5% of GDP into the military, by 2030 their military will begin to look scary and the other European countries will themselves dramatically raise their military spending to ensure Germany doesn’t get too much unopposable hard power. There was an approximate ten year delay in the 19th century, and I see no reason that there won’t be a similar delay in the 21st century – politicians hate making unpopular choices, so they’ll keep kicking that can down the road as long as they can. Still, when it comes to countervailing existential threats, European ruling elites do eventually grasp the thistle.

There are more resonances than just the above however:

The energy supply in the 1800s was transforming from human and animal muscle + wood + wind mix into a steam powered coal fed mix. It is hard to communicate just how profound that was – throughout human history slavery was the norm, not the exception, because it dramatically reduced the cost of the human muscle component. Coal and steam made it economically feasible for the first time in human history to abolish slavery. The ability of steam and coal to substitute for human and animal muscle had profound knock on effects throughout society, not least that average wages began to soar past the cost of barely surviving living for the first time in human history, as we shall see later.

These grand transformations move slowly enough to not be noticeable to most, however the 21st century is also experiencing a transformation of the energy supply from an oil and coal mix to solar PV, which means nearly zero cost electricity during daylight for half or more of the year. Human history has – until now – been one of constant energy scarcity. Even when oil was very cheap in the late 1960s, it was far from being practically free of cost. Solar PV enables genuinely free of cost abundant energy for the first time in human history (even if for only one third of a day), and it will be as profoundly transformative of human society as coal and steam was because we will be able to throw limitless energy at problems in some circumstances.

To give an example of what I mean, as readers may be aware, training AI is very energy expensive, however training can be costlessly paused and restarted around when the sun shines. While the sun shines, energy is free of cost, which means AI can be trained free of cost. That means ever better AI can be trained free of cost nearly infinitely into the future. That, in turn, means those humans best able to wield AI to increase their productivity will be able to demand wages many times more than other human beings. One can thus expect the wealth gap within the meritocracy to continue to increase, with all the profound effects that will introduce, especially as we increase the portion of society and government implemented with AI. It will be a brand new ‘automation wielding’ aristocracy very different from any historical aristocracy, and I am sure they will consider themselves to have a divine right to do whatever they think best as their power and reach grows.

Globalisation then was a tiny fraction of the volume of what it is today, but by 1820 things looked surprisingly similar to 2020 if you did a bit of squinting. By 1820, traveller’s cheques so you didn’t need to bring money with you during your travels had been widely available for fifty years. Would you like a ‘special order’ box filled with stuff chosen personally by you only available on the other side of the planet delivered to your door anywhere in Britain? Yes it would take months, yes it would cost a small fortune, but absolutely that ‘just worked’ in 1820. There were books of available goods in marketplaces all over the world, you could make a list and pay a broker to have somebody at that market obtain your special order, pack it and have it delivered to you, with that box passing through many human hands along well established logistic networks. I know that seems ‘so what?’ to modern readers used to Amazon and Aliexpress, but in all of human history, the periods where special order global logistics worked well are few: the Romans had it for a few centuries, the Mongolians had it for a few centuries, we’ve had it for a couple of centuries, but for most of history for special orders from afar – i.e. sourced from outside your own personal empire – you needed to send one of your men to physically travel there usually with a small army to protect the gold they had to carry with them to pay for the special order, and successfully physically return with the special order i.e. there was not a sophisticated network of brokers and middlemen available to implement seamless special order acquisition and transport. As one can infer, for such a sophisticated network to be sustainable, you need enough special orders constantly moving around the world, and you need sufficient trust between those many human hands that the system ‘just works’. Europe had regained that sophisticated network, having not had it since the collapse of the Mongolian Empire in the 14th century.

By far the most important special order from afar back then was information rather than goods. In 1814 the The Times of London purchased a new state of the art press able to print a thousand pages per hour. Such ever cheaper ever more voluminous printed newspapers aggregated information from all over the world, and disseminated it to an ever widening audience in a way which before 1800 didn’t really happen. This was enormously transformative – until then, only a few ruling elites had much idea of what was currently going on elsewhere right now. Now even a portion of the working classes knew what was happening in say Peru within four months of it happening. This would have huge effects in everything from the rise of Communism to awareness of the realities of war or famine elsewhere in the general population.

Today we have something similar but in some ways opposite happening, but for different reasons: from 2000 onwards there has been a rise of personalised entertainment, personalised information, and personalised world view. You can choose to live in a world full of only the stuff you like to see, and free of anything which might challenge what you already believe. Most have chosen that world, at least partially, and as people retreat ever further into islands of self reinforcing belief and faith it is going to be enormously transformative. Increasingly, only a few and shrinking ruling elites have much idea of what is actually going on across the board as the population’s beliefs and faiths become ever more detached from factual reality. That gives them more power than they have had in centuries, but it is also much harder to reliably use. That suggests more volatility going forth as peoples detached from reality grow ever more numerous and deluded.

In addition to the restoration of an aristocracy and de-education of the masses which are undoings in the 2000s of what was done in the 1800s, there are big economic differences between the 19th and 21st centuries, in this order:

- As alluded to above, the cost of information – especially timely

information – is so much cheaper today than then that I suspect its cost

hasn’t just exponentially decreased, but has hyperbolically decreased (i.e. the rate of decrease

was itself increasing e.g. exponential growth might be something doubling

every time period, whereas an example of hyperbolic growth would be doubling

first period, trebling next period, quadrupling the following period and so on).

I can, almost nearly completely free of cost to me, watch live 4k resolution

videos of a coffee machine on the other side of the planet. Or 3D cat videos.

Or how to construct a jet engine, or a novel retrovirus. Increasingly, I

don’t even need to read instructions in technical jargon, I can have an AI

explain them to me in words I understand and quickly act upon.

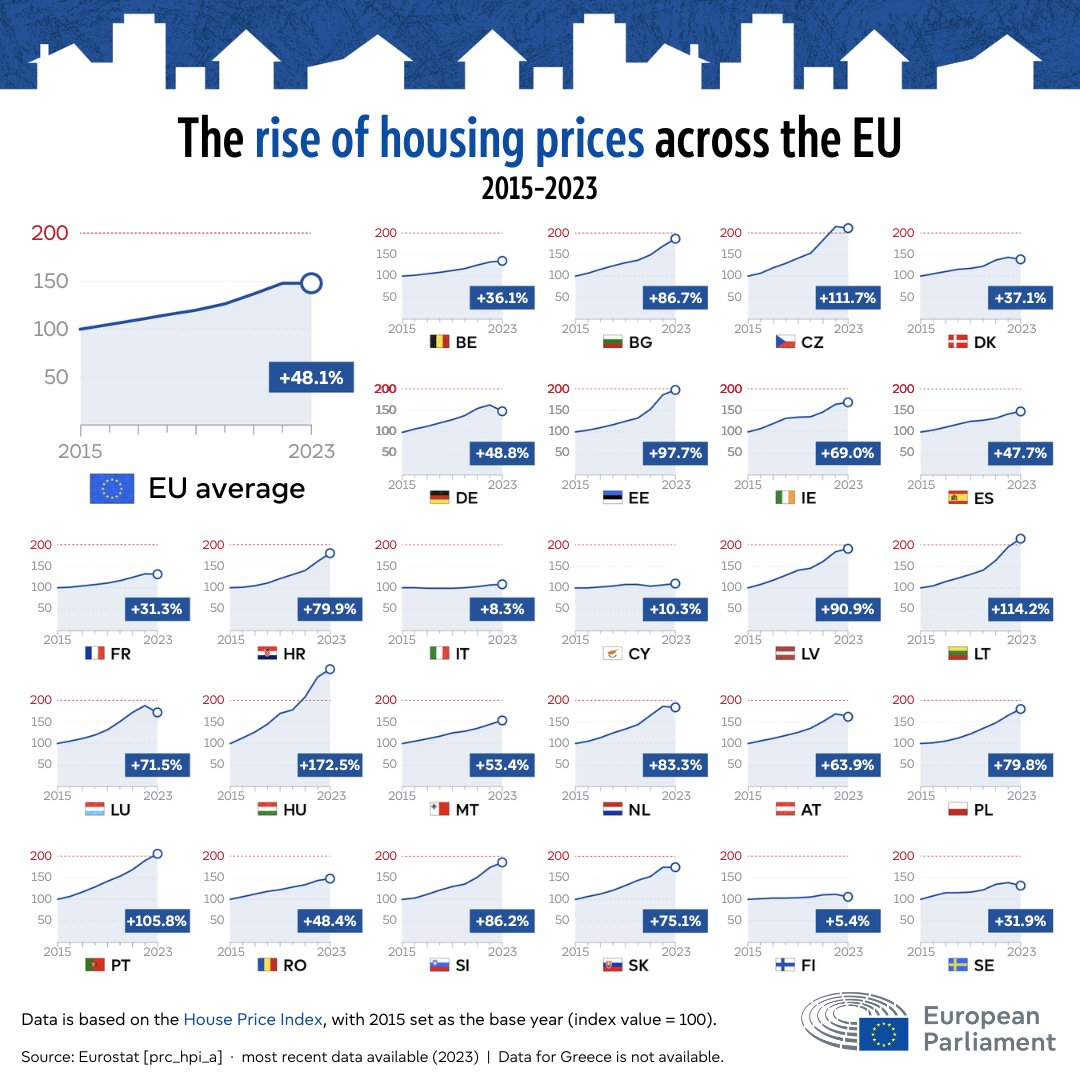

- Two of the basic costs of living – food and clothes – are exponentially

cheaper today than then. In the 19th century, food and clothes made up a

significant portion of the cost of staying alive – today, at least in the

three major regions of power Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia, housing costs

have returned to early 19th century levels in the past twenty years, but the

other two costs of food and clothing are dramatically lower.

- The cost of finished goods is a fraction today of then, and the multitude

of labour saving and leisure goods available today simply weren’t available

for ANY money back then.

- As we’ll be getting into more of later, the cost of labour is far higher

today than then. True, today’s labour is also more economically productive

than then due to a better skilled workforce and the more widespread use of

automation, but if you say, wanted to repair a portion of road, back then a

moderately wealthy person could pay for it out of their own pocket without

thought. Today, it would cost a good portion of an annual income, which is

why only governments and corporations now pay for road repairs. This shift,

as we’ll see later, will be important.

- There was no such thing as minimum wage nor collective bargaining

agreements nor unions. Everybody got paid what the market felt they ought

to in cities, and what the paymaster thought they could get away with (i.e.

far lower) outside cities. This meant huge income gaps by today’s standards,

but also huge relative increases in pay with seniority compared to today –

most people would see a quadrupling or more of wages during their working

life, even for low status jobs (though with those, the wage increases were

compressed into young adulthood, whereas for high status jobs incomes kept

periodically doubling with seniority until retirement). There was no pension

system nor health

insurance apart from what you personally saved for yourself, so you had to

save a good proportion of everything you earned like today’s average

Chinese citizen does to provide for your old age. This means a surplus of

savings which tends to cause price deflation.

- Taxes in the 19th century were extremely low by today’s standards. As

mentioned earlier, the central government mainly earned from tariffs and

duties on goods which crossed a border; local government and local public

goods such as roads and bridges were paid for principally by the wealthy

members of each burgh or parish, but also by local taxes on income. Each

burgh or parish outside the major cities could do its own thing in 1815,

and naturally enough those places with lots of rich people tended to have

much better public infrastructure than places with few rich people. As the

19th century progressed in Britain, the modern administrative state emerged

along with modern levels of taxation, which had a profound effect on my

wealthy ancestors, as we shall see.

- If you sum all of the above, life back then was far more winner takes it all than today. There was little to no social safety net – if misfortune like illness or accident happened to you, it was usually game over not just for you but also for your dependents. Equally, if you were fortunate, nobody skimmed off your gains and you got to keep it all.

What AI thinks represents 'deflators'. I like how it chose to put a crucifix over the Greek columns!

This brings me into deflators because reporting money values from long ago in terms of money values today is a tricky problem. As you can guess from the just described differences in changing of costs of living, depending on what you are describing changes how you calculate today’s equivalent money value. There are three main deflators maintained by the Bank of England over time:

- Retail Price Index

(RPI) deflator which is a measure of the cost of living

for the average worker. It tracks a basket of typical goods over time but

also the cost of rents. This is closest to the modern use of ‘inflation’,

though it is typically about 1% per annum higher than it ought to be due to

how the quality of the items in the basket are handled (e.g. today’s bread is

definitely not the bread typical in 1815). Britain has a very good historical

RPI dataset going back to about 1300, and it’s quite accurate from about 1600

onwards thanks to the efforts of Bishop William Fleetwood

who calculated price indices for inflation 1440-1700. This is

the right deflator to use for food and clothes, it is less

suited for rents, and it is the wrong deflator for most other things.

- Earnings deflator,

which tracks average wages for the average worker over

time. So, for example, a manual labourer might earn £5 per year in 1815, but

today they might earn £30,000. This is the right deflator to use for wages

and sums of money relative to wages, though it suffers from how the basket

of jobs in the past is very different in quality and quantity to today’s

basket e.g. a cook back then is definitely not like a cook today who would

need certified training in sanitation etc.

- GDP deflator, which tracks share of the total product of the British economy over time. This one is a bit harder to describe, but essentially it’s a measure of ‘relative economic power’ to the economy of the time. If your wealth was one quarter of the entire British economy in 1815, the relative power of that wealth would be the same as a quarter of today’s entire British economy. This is arguably the least worst deflator to use for very large sums of money which are at nation state relative levels e.g. if you own half the land of Scotland, your wealth back then ought to use the GDP deflator to map onto a reasonable valuation today.

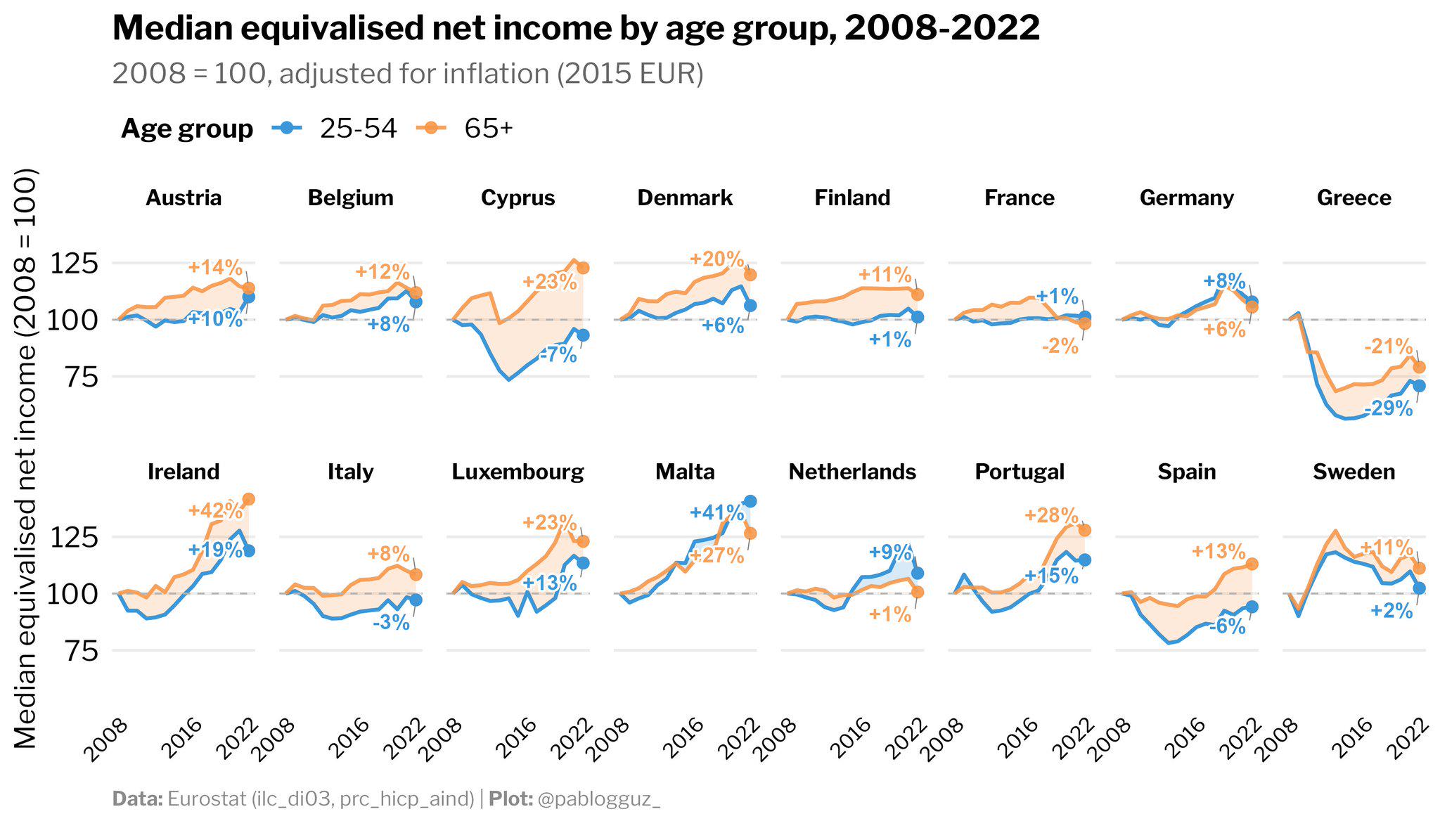

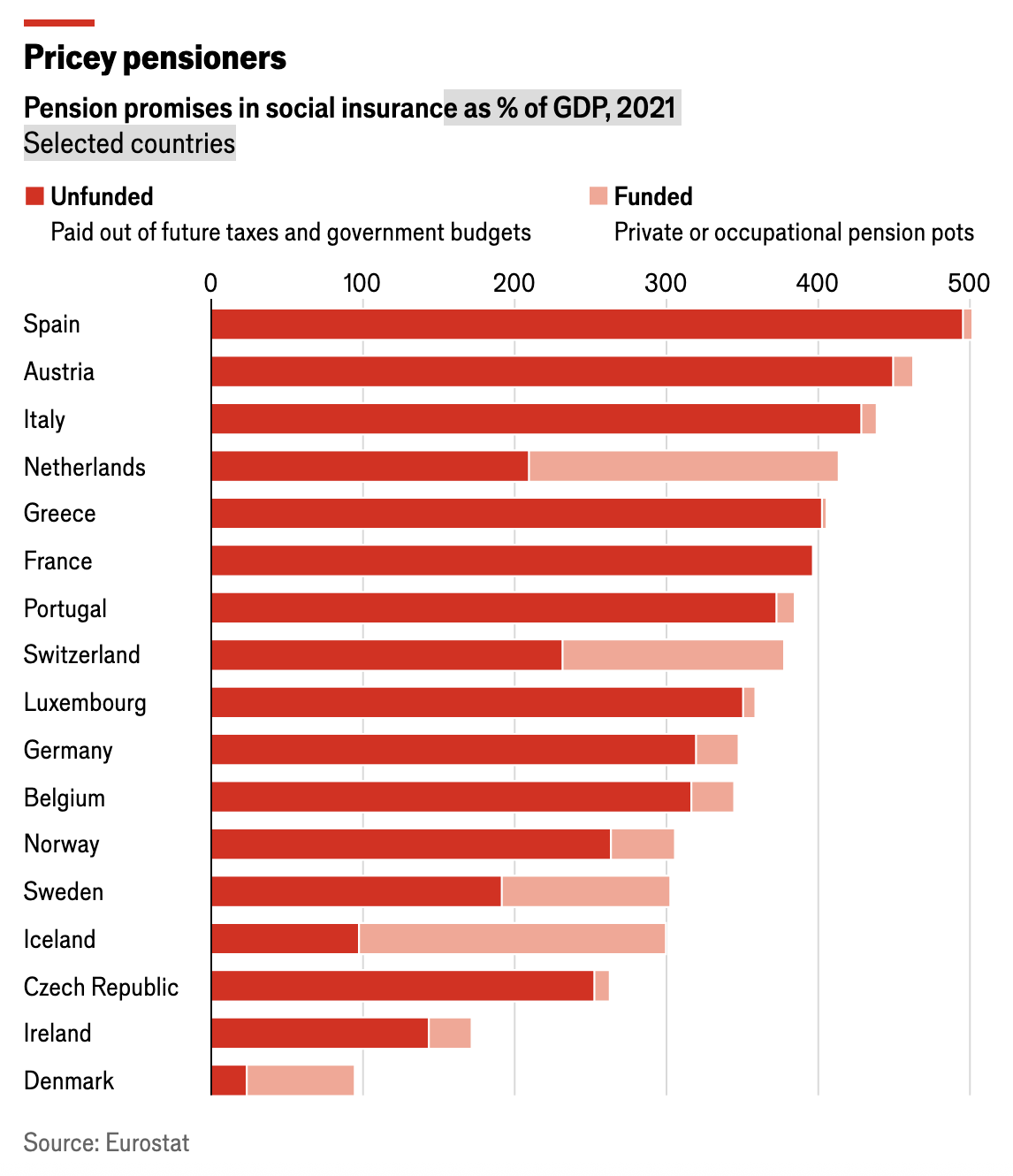

Those are the three basic deflators, and by definition all are for the average case and will always be wrong for any specific application. In the coming text I’ll say which deflator I’m using (usually the wages deflator), and just to visualise things here are the three deflators 1815 to 1915 relative to 2024:

RPI varies a lot by year based on harvests, so I applied an averaging across ten years. Note that the cost of food, clothes etc fell 1815-1895. This period from 1873 onwards is known as the ‘Long Depression’, and you can read more about it here. China is currently in a ‘Long Depression’, it is caused by overinvestment in factories, so where the factories are (today: China; in the 19th century, it was Britain), you get the worst cost of living deflation. Deflation is not good for economic growth – it also tends to create angry and dissatisfied populations which induces instability and tends to eventually promote warmongering.

Nominal wages were roughly flat between 1815 and about 1860, however then they shot up between 1862 and 1872, then the beginning of the Long Depression held them flat until 1890 after which they began shooting up again. This was great for wage earners who captured an ever larger slice of the economic pie, but it was bad for the section of wealthy just below the ultra-wealthy class as employing people consumed more of their resources (to explain: the ultra-wealthy deflate by GDP, whereas the normal wealthy deflate by wages, this is why the gap between the ultra-wealthy and the normal wealthy tends to grow over time).

Nominal British GDP shows an exponential growth throughout the period, despite the Long Depression. This is similar to today, where GDP keeps rising but most citizens do not feel that their quality of life is improving – if anything, they feel the opposite.

Finally, you can also make the wages and GDP deflators relative to RPI, which means you can see wages in terms of how much food and clothes it buys, and share of the total economy in terms of how much food and clothes it buys over time. This can be revealing:

Wages, in terms of how much food and clothes it would buy, showed far more relative growth between 1815 and 1868 than nominal wages alone. They then enter a strong period of growth during the Long Depression until a clear inflection point at 1899 when the Long Depression ends, after which wages bought fewer clothes and less food each year up to and including World War I. This was due to the beginning of remilitarisation from 1899 onwards shifting resources into military production: the average earner got poorer in real terms as the economy made weapons instead of making the average earner richer. We should see the same in the next decade when the whole of Europe begins to remilitarise in earnest – the cost of food and clothes will rise faster than wages as workers are reallocated into military production. I’ll come back to this at the end of this essay, but for now accept that widespread peace tends to create low price growth, whereas preparing for war and especially war itself tends to create high price growth.

RPI adjusted GDP still looks exponential, but more smoothly so – there is no longer a ‘bump’ around 1870.

Ok, with all the preliminaries and stage setting now complete, let’s get into it: I’ll take each decade in turn, one by one, and from that draw some conclusions.

1810s

You will remember how earlier my ancestor and sugar plantation owner Walter Irvine (1747-1824) had come to consider my ancestor Lord William Robert Keith Douglas (1783-1859) as a potentially suitable husband for his eldest white daughter, Elizabeth Irvine (1798-1864). We know that William as needing to find a means of livelihood had been doing something around trading in London and he was appointed by the Duke as Member of Parliament for Dumfries in 1812 at the age of 29. Walter had had no surviving male heirs with his wife Catherine Gordon, and for some reason he considered his nephews trustworthy enough to manage the estate for his daughters but not to inherit much of those estates. In any case, it seems he decided that he would effectively adopt a chosen male heir in whomever married his eldest white daughter. He appears to have taken this most seriously: his final decade of life appears to have been largely dedicated to ensuring that his children would be taken care of. It would appear that Walter Irvine came to an agreement with Lord William Keith that if he married his daughter Elizabeth and performed certain actions in perpetuity, they would receive one third of his fortune and the remainder of his estate would be geared toward supporting them before all others e.g. if other recipients died without issue, their estates would revert to Elizabeth Irvine, and therefore under William Keith’s control.

We know that Walter Irvine had taken residence near his father’s lands no later than 1815, as he is listed as a head of household for Denino in the Edinburgh Almanac for that year. We know that he purchased those lands off a Thomas Bruce of Grangemuir, who appears to have needed to sell most of his Grangemuir estate due to financial difficulties – he retains some of them where he resides until his death sometime after 1824. We think that the lands were purchased in 1806, and we think the modern Grangemuir House began construction in 1807, replacing an earlier ‘haunted’ house to its south which was demolished. Thomas Bruce, the former owner, is said to have performed the build, and we know he was highly trusted by Walter as he was one of the five trustees in his will. That house, and their surrounding lands, were then gifted to Lord William Robert Keith Douglas and his wife when they were married in 1821 within their marriage contract. She was aged 22, and he was aged 38. Here is the house a little after 1830, when William Keith and his wife built a substantial extension to the right of the building which made the house no longer symmetrical:

Thomas Bruce of Grangemuir is an interesting fellow. I think he is a second or third cousin of Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin who pilfered the Elgin marbles from Greece. That Thomas Bruce would have resided in Broomhall House, just down the road to the south-west of Grangemuir in Dunfermline. As you can see in the picture of their mansion house below which puts Grangemuir House to shame, they had rather a lot of money:

Thomas Bruce of Grangemuir definitely did not own the lands around Dunfermline, and definitely was more distant than first cousin to the Earl, but he did own the lands just east of the Earl’s lands which were Grangemuir. He had inherited them from the original owner Sir William Bruce of Balcaskie, probably the most famous architect in Scotland in the 17th century, who was not a lineal ancestor, and they had passed to him via a circuitous inheritance route due to several relations dying without issue. This Thomas Bruce of Grangemuir had debts and so needed to work, which was as a Director in the Hercules Insurance Company (which is today part of Lloyds). Walter Irvine thought very highly of him, not just entrusting the rebuild of Grangemuir House but also the co-management of his estate after death and the guardianship of Walter’s youngest daughter who was yet to come of age. Thomas appears to have served in every public service position possible in his region: he was a Magistrate, Fireman, Tax Collector, Duties enforcer, Bridge Inspector, head of Train line maintenance, and of course served on the parish and burgh boards of management. He was even, when younger, part of the local militia and coastguard. He seems to have endless reserves of energy – he also wrote copious letters and petitions on the behalf of his region. He appears to have been the ideal local matters activist, and I assume that this is how Walter Irvine both knew him and why he had such high regard for him.

Returning to the marriage of William Keith and Elizabeth, there was a very extensive marriage contract running to dozens of pages of conditions, requirements, and penalties if certain things were to happen, or not happen. One explicit condition is that W R K Douglas could not sell the sugar plantations during his lifetime – indeed, they were to return to Elizabeth Irvine upon his death and could not be willed elsewhere except by her and her alone. He is also required to act on their behalf as a Member of Parliament, so from 1820 onwards he becomes one of the two principle advocates acting on the behalf of the Caribbean plantation owners to the British government. In 1824, just after his father-in-law’s death, he is appointed to lead the West India planters and merchants standing committee. That standing committee still exists today and is, believe it or not, still doing its original purpose of representing the Caribbean island interests to the British government. You can find its website at https://westindiacommittee.org/about-us/.

I have read through most of Hansard’s records of any debate in which William Keith participated. As with most Parliamentary discussion today, it does not render politicians in a good light. They are generally far keener to score political points than have a productive discussion. In the records of what was said in Parliament, there generally was a person who wished to free all the slaves immediately, another who felt the biggest problem with slavery was the lack of whipping and hangings, and my ancestor William was usually one of the moderate voices in between the extremes. It was hard to choose a typical example of such impoverished debate, but I landed on this example of Parliamentary discussion in 1831 as reasonably representative of the abased discussion. While yes I’m getting ahead of myself, I can tell you that the level and calibre of Parliamentary discussion around slavery was pretty consistently low quality between the Slave Trade Act of 1807 and the Slavery Abolition Act of 1835, and it wasn’t edifying, as that representative example shows.

The last big thing to happen in the 1810s which is relevant here was the Importation Act of 1815, better known today as the Corn Laws. This was a sweeping set of high tariffs introduced on the importation of most food stuffs (not just corn). The principal motivation was needing to pay off the debts of the just completed Napoleonic war, but a secondary motivation was to keep agricultural produce prices high within Britain as the growing empire had been supplying imported food so cheap that British native farmers were in deep financial trouble. Obviously, intentionally raising the cost of everybody’s food was not popular, and the Corn Laws became a major political football until their repeal in 1846.

1820s

This is Lord William Robert Keith Douglas and his wife Elizabeth Irvine. These photos were taken late in their lives, probably in the 1850s:

Lord William Robert Keith Douglas (1783-1859) |  Lady Elizabeth Douglas-Irvine (1798-1864) |

My ancestor William Keith and his new wife Elizabeth Irvine take up residence at Grangemuir, Fife after their marriage in 1821. William Keith remains MP for Dumfries which is the other side of Scotland, and of course he must also regularly get to London to attend Parliament. So he isn’t home for much of the year as far as I can tell, and doesn’t manage to get his wife pregnant until 1824 which is the same year that Walter Irvine passes away.

Until a few days ago, we were not aware of the full contents of Walter Irvine’s will which runs to some thirty-two pages (the best we had until now was the UCL’s partial transcription). It was written in a particularly indecipherable hand written script, and it was too tedious to transcribe. However, a few weeks ago I spent four hours feeding it into a state of the art AI trained on 18th century hand written legal documents and we finally got out a high quality transcript. I then fed that transcript into an AI to have it fix up the most probable transcription errors, and then to turn it into modern English, because the original is rather a spaghetti of self inter-reference and is quite hard to decipher without a fair bit of study and note taking. To be honest, without the kinds of AI developed only these last couple of years, that will was going to be more effort than any of us were willing to expend, and finally revealing its contents has been truly eye opening.

Walter Irvine goes into very great detail about how his fortune is to be managed and invested and allocated after his death. He creates annuities with fixed or variable annual payouts for a long list of people including two of his slave born daughters Betsy and Mary, and requires the capital to be invested in securities bearing 3% or more per year to ensure that the capital would be preserved over time. He entrusts the management of his estate to these people, and three of them are required to reach consensus to perform an action:

- Elizabeth Irvine, eldest daughter (in those days, that meant her lawful

husband, as only he could act on her behalf so long as they remained married,

but Walter wished to be clear that if her husband died it would be her who

regained control before her eldest son).

- Alexander Gordon, brother of Catherine his wife (and therefore uncle of

Elizabeth).

- John Hamilton of Hampshire (I could find nothing about him on google,

though he may be a younger brother of a set of famous army Hamiltons of

Hampshire)

- Christopher Irvine, nephew and son of his deceased brother Charles, who

still resides in Tobago as a plantation owner.

- Thomas Bruce, original owner of Grangemuir previously described.

As unusual as it was to entrust such an estate to non-family members, the will is also clear that the eldest son of all these was to inherit the role after their father died, and their eldest son thereafter, so long as they were in the line of primogeniture. If there were no sons, the other managers were required to choose a suitable replacement.

While the minor annuities had to be invested specifically in 3% bearing British consols, the two really big annuities of £35,000 for each of the sisters Catherine Grace and Christina Charles were to be invested in the stockmarket in investments chosen by the trustees, which will be significant later. The remaining third of the estate was made up of Grangemuir House and Lands, and the sugar plantations in Tobago, which went to Elizabeth Irvine to be managed by her husband William Keith. Curiously, he mandates that if Grangemuir and lands became valued one third below their original value, the Tobago estates were to be sold to bring Grangemuir back above the value. Grangemuir and lands were required to invest their proceeds after running costs in new properties built anywhere in England, Scotland and Wales bearing rent, and nowhere else was allowed. The trustees couldn’t invest the profits in gold, as an example, because it wasn’t a physical building bearing a rental income. This would prove calamitous later, as we shall see. However despite the onerous restrictions placed on William Keith and his wife, the trustees themselves were granted (by the standards of the day) remarkable freedoms to invest the annuities in anything they saw fit, and to bill the estate for a very wide range and type of expenses.

That’s a pretty remarkable will between the granting of large sums to slave children and such a long term big picture worldview. But it gets better again: the will has considerable detail about how his daughters are to be treated by any future husbands (specifically: any husband will gain no rights to claim his wife’s assets nor income nor be able to tell her what to do with her annuity income, plus her assets are to be willed to others solely by his daughter and husbands cannot override the choice), with detail about what happens if the daughter remains unmarried or her or her husband dies with or without children. Interestingly the slave born daughters got different rules to their white sisters (less strict and more empowering). This modern liberality about the rights of women was very unusual at the time, but it makes sense – his father worked at the Court of Chancery which back then was the leading advocate of, and indeed granter of, equal rights over property for women as men. Walter, having grown up around dinner tables full of Chancery Court debate, would have been unusually liberal on this subject for the time.

Wills of large estates have always been long and detailed, but this will barely mentions the distribution of the wine, liquor, silver plateware, art etc collections which would be more typical in wills of the time – and indeed were the case for the wills of his descendents, who focused far more on who got what rather than telling people how they were to behave for the next century. Instead it presents a sweeping vista of investment targets and required outcomes and a quite astonishing level of trust in some people, and not in others. As this will is so unusual, I have placed its full original text here (note that this is the AI cleaned up edition) and the AI summarised edition here:

- The Transkribus AI parsed transcription of the original, cleaned by Claude AI

- Claude AI’s summary into modern English of the original text

I have no way of knowing, but the will comes across to me as coming from someone on the autism spectrum. The unusually favourable positive treatment of women, the explicit granting of considerable wealth to slave born children which he makes no attempt to hide the provenance thereof, the profound faith in a set of Scotsmen AND their lineal descendents. Also, why purchase Luddington House in Surrey when he could have afforded any house nearer London? Luddington House is very obviously just far enough off the beaten track to put off casual visitors. The only people making the journey would have cared enough to make that journey. But he was still close enough to London that it wasn’t completely inconvenient. This could have been a highly controlling man, there is plenty of evidence to support that, but I got the feeling from the will that Irvine genuinely thought he was being useful to everybody after his death by writing out all the rules and requirements for what they had to do in laborious, extensive, detail, and giving them a type of freedom and trust to enact his vision. That’s aspergic at best.

In any case, Walter Irvine’s total estate in 1824 was £120,000 which is £144 million in 2024 under the wages deflator. Of that, we reckon about £40,000 in total immediately went to William Keith and Elizabeth Irvine in the form of Grangemuir House and 2,700 acres (11 km2) of surrounding lands occupied by tenant farmers. At the time, £4,000 (£4.5 million) was yielded annually in rents, a 10% yield. The Tobago estates and other cash transfers I estimate made up a further £10,000, so the newly wed couple began married life with perhaps a wealth of £50,000 or thereabouts.

In the 1820s, there was a national tax on tenant rental income of maybe 3-4% which was a 5% tax but based on 17th century valuations (it’s a fascinating example of how dysfunctional British property tax has been for four centuries now, you can read more and weep at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_Tax_(England)). There was an inheritance tax on large estates of about 1%. Other than those, the state didn’t really involve itself in local affairs or anybody’s financial affairs except in times of war, when extra money was raised to fund the war. The local landowner was responsible for public goods such as roads, drains and walls as well as the upkeep of the housing and workshops rented out by his tenants (indeed, Walter Irvine’s will lists £217 owed to him by people building roads in lands adjoining Grangemuir). They didn’t pay for all of local schooling, that technically fell under the church, but were expected to contribute a large share of the running costs for both church and school. If the land had problems with crime or was at risk of invasion, it was expected that a militia be maintained – similarly, most burghs had a firefighting service made up of local strong men. Usually the landowner was also a Magistrate, and therefore also judge and jury for most minor crimes and participated in discussion of local decisions with the other landowners. Life generally revolved around the farm, the church, sometimes the representatives employed by your Lord the local land owner, occasionally the Lord and his family himself in person, and most people never knew much past those up until the 1820s.

Grangemuir House was a modern design and build, and likely did not require as many staff to run it as older buildings would have required. I’ve estimated six full time staff: a cook, a coachman, a gardener, a lady’s maid and two scullery maids. If there were young children, you would add a tutor and a nanny, and when the national census came in, we do see eight staff generally speaking. In any case, I reckon the annual wage bill was about £178, or about £200,000 in 2024 money according to the wages deflator.

The 1820s were closed out with multiple births: after William in 1824, Walter was born in 1825, Catherine Grace in 1828 and Elizabeth Christian in 1830.

1830s

What AI thinks the 1830s looked like

By 1832, it had become obvious that slavery was going to be abolished soon across the British Empire after an especially brutal repression of a slave uprising in Jamaica in 1831 – all that remained was the details of how. The rotten borough system of rich landowners choosing the Member of Parliament was done away with in 1832, and William Keith seems to have concluded that representing the West Indian planters as a Member of Parliament had become pointless (he certainly had singularly failed to have had any effect whatsoever). His patron, the Duke, had become increasingly displeased with his choice of MP in any case, so in 1832 William Keith chose to retire from active politics which also meant he could spend far more time in Grangemuir with his small children rather than shuttling between Dumfries and London. He was forty nine years old, which is one year older than me right now.

Hansard reports that William Keith was not keen on slavery throughout his Parliamentary career, and began publicly hinting as such especially towards the end of his active political life. His speeches on the proposed abolition of slavery were usually about the importance of not letting slave owners off the hook of taking care of their slaves in any proposed reform – a typical spoiling argument used by politicians to make themselves look moral and upstanding – but in his case he seems to have genuinely despaired at how the future Slavery Abolition Act was taking shape, and he had no wish to participate in its passage. Indeed, he famously (at the time) failed to vote either in favour or against several late stage motions around that Act, which caused some abolitionists to publicly claim that he was actually secretly a fellow abolitionist. In any case, it meant the end of the West Indies economic model, so his deal with his father in law to represent at Parliament his estates was now moot. He does seem to have been in a sorrowful mood from his public speeches in 1832.

The 1833 Slavery Abolition Act is infamous for having the British government borrow a very large sum of money (about 5% of GDP) to compensate the slave owners (not the slaves!) for the loss of ownership of their slaves. That portion of the British national debt was paid off by British taxpayers until about the year 2005, so it was a big reallocation from everybody else to a few wealthy slave owners. It wasn’t popular at the time not least for the moral and properness argument, but it did buy the quick abolition of slavery. There were some token requirements in that Act that owners had to aid the transition for their slaves, but it had zero enforcement, and unsurprisingly many slave owners simply abandoned their slaves some of whom then starved to death. From 1823 onwards the Caribbean sugar plantation industry had been in terminal decline, so from those slave owners perspective there was zero point in spending any of the compensation money on loss making estates. It didn’t help that by then most slave owners were the merchants who shipped the sugar rather than the planters who originally owned the land, which due to recent bankruptcy of the planters their debts to the merchants had been often paid with their land and slaves, and so now the dominant receivers of the slave compensation money were the merchant houses who did the import of goods into Britain. Those merchants, who only cared about minimum supply costs to them, typically employed attorneys to manage things locally and it was widely accepted at the time that the worst abuses of slaves were almost always on merchant owned estates. We know this because occasionally the abuses were so bad that public inquiries were launched which means there was public outrage which was documented at the time in the form of a published report. As with most British public inquiries today, little was done about their recommendations, but their records were made public and they are a useful source of historical information.

At least in the case of William Keith’s estates the slaves didn’t starve to death after abolition. The Tobago historical society has detailed accounts of the time, and Tobago has conducted extensive academic research. More than two thirds of the slaves on his estates elected to remain as self employed share croppers, with mainly the young adult slaves moving to the city for better work opportunities, with some evidence that they returned periodically to visit their parents e.g. for holidays or festivals. It helped that Irvine’s estates had by then been extensively automated to reduce the burden of manual labour, with William Keith having built in the 1820s the largest sugar mill on the island which is now the restaurant of the hotel described above, with the windmills and waterwheels and some early steam powered mechanisms still present today on the grounds as features. There was also a basic school and a church on the estate, and housing appears to have been above average in quality. It would seem that William Keith retained ownership of the land and machinery, and charged an annual rent to the sharecroppers who were now tenant farmers like those in his Grangemuir estates. This was exactly the model he had advocated for years speaking in Parliament, but had failed to persuade Parliament to require it in the reforming law. The Irvine descendants did later receive £11,000 as compensation under the abolition act, which is £12 million in 2024 money under the wages deflator.

The other significant thing to happen in the 1830s was the Burgh Police Act of 1833 (it was quite the year for reform in all areas all at once!). This began the process of creation of local authority councils to manage and pay for public works and services. This act only applies to large cities, but as we shall see later it widened from there.

Also in the 1830s were the births of the last of his children: Mary Louisa in 1834 and Charles in 1837. He was fifty-six years old when the decade ended.

1840s

What AI thinks the 1840s looked like. Note the amusing hallucinations!

In 1841 under the powers of the Burgh Police Act, a police authority was established in Pittenweem burgh just adjacent to Grangemuir. Around this time burghs and parishes were being strongly encouraged to set these up. The modern meaning of ‘police’ is the kind which catches criminals, but back then a police authority was what we’d call today a local authority, or council. One of its many functions was to prevent crime, but it mainly concerned itself with other public services such as bridges, roads etc.

To pay for this burgeoning local authority system, an income tax for wealthy people at 2.9% was introduced. This was the first time an income tax was levied outside of wartime in Britain, and it would turn out to be permanent. This raised the total taxes on income for this branch of my ancestors to about 7%, small by today’s standards, but a doubling of taxation at the time.

Household staff probably cost £188 in this decade, up from £178 in the 1820s. In fact, the head butler of the household, a Thomas Pitkin, was married to one of the maids Sarah Hill and they decided to relocate with their five children to Australia in 1841. Apparently William Keith gave them a very good send off, the Pitkin family lore spoke very highly of my ancestors according to the Pitkin descendants I spoke to many years ago.

1846 was quite the year! Perhaps none in recent British history outside of declaring war was quite so profound. Firstly, with their hand forced by two years of famine in Ireland causing a reduced supply of grain and riots due to hunger, the Corn Laws are repealed, causing the price of agricultural goods to slump which was excellent for most people as food dropped dramatically in cost, but very bad for farmers and their landlords and the viability of the rural British economy (which continues to this day). Interestingly, William Keith was in favour of the repeal, despite the obvious impact to his income (he seems to have felt free trade better on balance overall). Secondly, in the exact same year, the potato famine began in Scotland having arrived from Ireland, which multiplied the negative immediate effect on landlord wealth, as they were responsible for mitigating the famine as the land owning class. Elizabeth Irvine, reputedly a very dour woman, appears to have had a particular thing for helping the poor like her sister Christina and her mother Catherine. The family moved into the servant’s quarters, and the main house is put to use as infirmary to the starving. Elizabeth personally acts as nurse on daily rounds to this multitude who were housed in all available properties and fed at the estate’s expense. This housing of the multitudes lasted about three years according to the records, with the famine ebbing and returning in bursts until about 1852. Thirdly, the British stockmarket begins to collapse due to the bursting of a railway mania investment bubble from 1846 onwards – many middle and upper class households lost a fortune. Finally, to make this period an especially bad one for my ancestors, the sugar plantations in Tobago were heavily damaged by the hurricane of 1847 and the 1847 collapse of the West Indian bank, from which they never recovered profitability, especially due to the 1846 Sugar Duties Act which had made Tobago sugar production uneconomic. However, due to the terms of Walter Irvine’s will, the estates could not be sold, and would from now on probably cost more than they yielded.